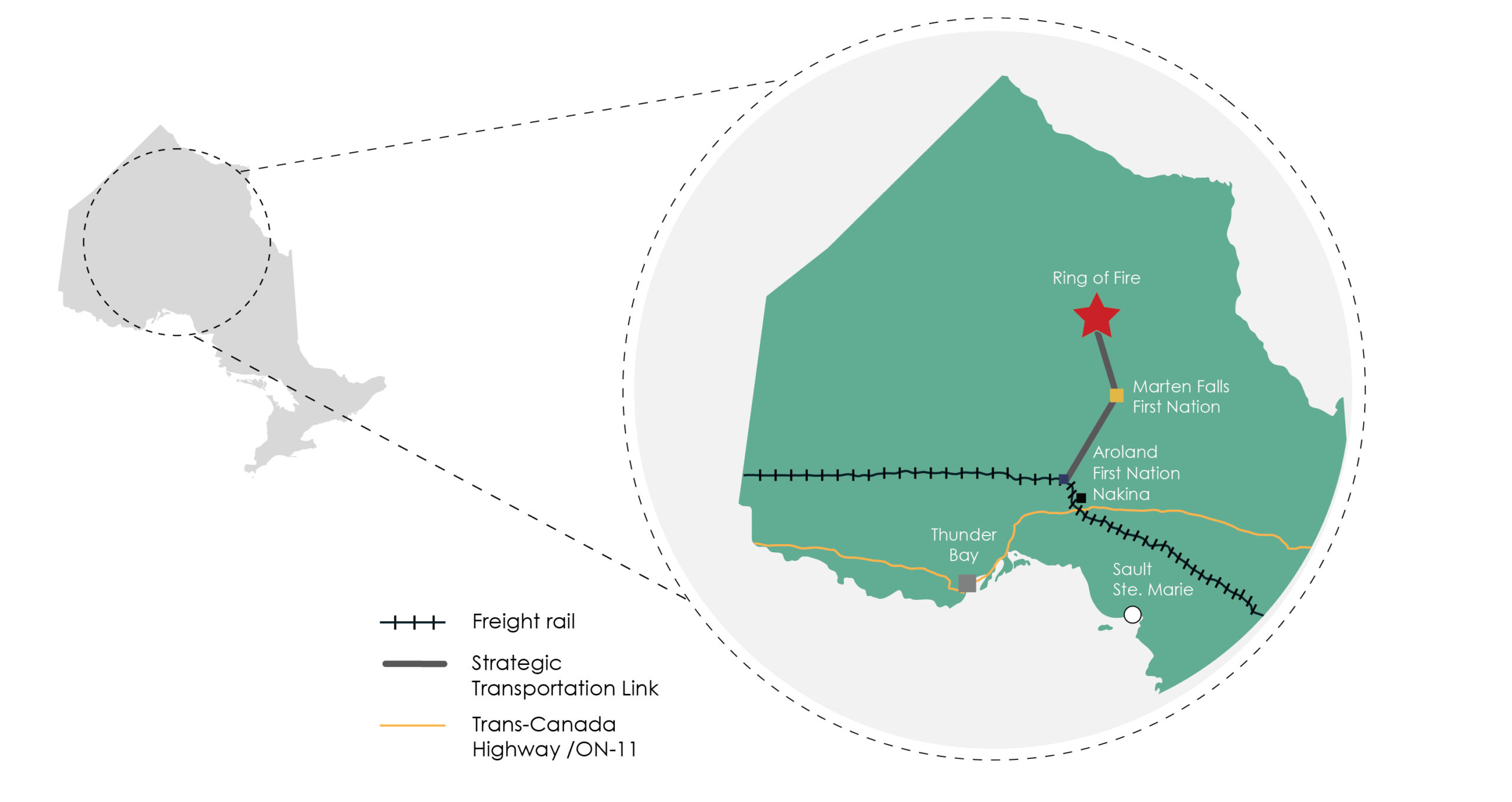

Roughly 500-kilometres northeast of Thunder Bay, or about 1,000-kilometres north of Toronto, lies Canada’s largest known source of untapped mineral wealth. Rich in chromite, copper, nickel, gold and zinc, Ontario’s “Ring of Fire” stretches across an area larger than 5,000 square kilometres. Deposits of palladium, platinum and vanadium are also present. These materials are critical inputs to just about every facet of our modern lifestyle, from the stainless steel in our cars to the electronics of our smartphones.

This ecologically sensitive land traverses the traditional territory of several Indigenous communities and should only be accessed in true partnership, consultation and shared prosperity. A key challenge for all involved is the area’s remoteness to existing transportation infrastructure.

Development of most of the minerals in the Ring of Fire will require year-round, land-based transportation links. Weather conditions will no doubt affect construction, and the surrounding landscape presents innumerable swamps, bogs and waterways. But this geography is not insurmountable. In the late-1950s, the midway section of the Trans- Canada Highway through Ontario, known as “The Gap”, presented similar engineering challenges.

Ontario’s relationship with its Far North for a century. It presents opportunities to work alongside Indigenous communities to ensure environmental impacts are considered, land rights are respected and economic benefits are realized equitably. Many First Nations in the Far North do not have year-round, landbased transportation access. Marten Falls First Nation, about halfway between the Ring of Fire region and the region’s existing transportation links, only has winter road access, and the season is shrinking. This is unreliable and inhibits access to core necessities, such as fuel, medical supplies and healthy food.

Multiple routes have been proposed to connect the Ring of Fire to existing transportation corridors and to industrial markets where mineral processing could take place. A strong case can be made for the Province to lead the construction of a north-south road from a location near Aroland First Nation and the Township of Nakina to Marten Falls First Nation. Aroland and Nakina are situated northeast of Thunder Bay and are already near existing highway and rail infrastructure. This would be a practical first phase of a potential two-phase construction project to reach the Ring of Fire.

The project is in the early planning stages, and there are numerous factors to explore before construction begins. Some communities, such as the Webequie First Nation and Nibinamik First Nation represented by the Matawa Chiefs Council, have stated publicly they would support development so long as the Council was an integral party in all discussions. Other communities want to see more specific details and proposals. OREA supports this potential project on the assumption that the Province and private sector would proceed in partnership.

A north-south corridor would increase the likelihood that mineral processing takes place in Ontario, bringing more of the extracted resources to within closer proximity of Ontario’s northern industrial clusters. It would also open up access to other natural resources in northern Ontario, such as forestry and wood products. Given the Ring of Fire’s vast potential, numerous other benefits would reach every corner of Ontario.

The Province should continue to engage the Government of Canada, the Canada Infrastructure Bank and the private sector about the funding contributions necessary to make the project a reality. It should also continue to participate in meaningful consultations with Ontario’s Indigenous communities and ensure that rigorous environmental and regional impact assessments are conducted.