The Niagara Peninsula is a trade superhighway. On average, prepandemic, 1,600 trucks and 5,800 cars crossed the Peace Bridge each day between Fort Erie and Buffalo.

Congestion on the QEW, the Peninsula’s only major roadway to and from the border, is a major strategic challenge. The highway is near capacity and expansion isn’t tenable. Physical constraints, such as those imposed by the need to protect some of Canada’s most valuable agricultural land, limit expansion. In addition, Niagara Region’s total employment is forecast to swell by 30% over the next 25 years. A new route is needed and planning for it must resume today.

Our economic competitiveness depends on the efficient movement of vehicles across the border, but it also depends on getting cars and trucks to and from the border. Since the implementation of NAFTA in 1994, Canada-U.S. trade has increased dramatically. Niagara’s bridges and highways haven’t kept up. We are living with pre-NAFTA infrastructure in a post-NAFTA world. Canada’s reliance on international supply chains became even clearer during the pandemic. We must address our border infrastructure to support resilient supply chains.

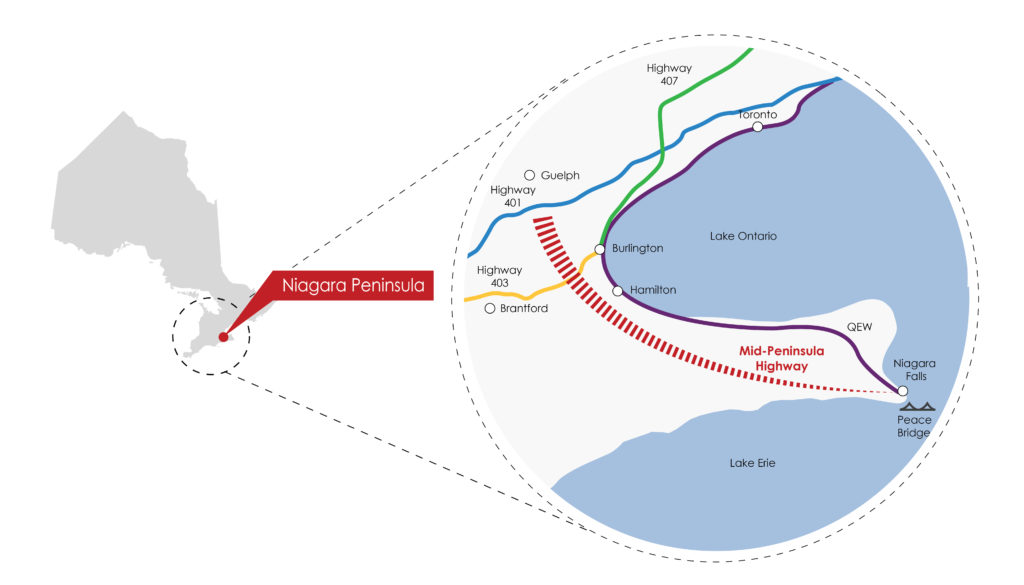

A new freeway, often referred to as the Mid-Peninsula Highway, would create a supplemental transportation corridor to the QEW between the western GTA and the U.S. border. At its core, this project is a 100-kilometre long route that could extend as far as Highway 403 near Hamilton, Highway 401 near Cambridge and Highway 407 near Burlington. Improved access to Hamilton International Airport would also bring system-wide benefits, providing direct passage between regions in the Southwestern Ontario Airport Network and for the provincial economy, improving regional connectivity. This will enable efficient movement of goods and people, but also will foster increased prosperity between Hamilton-Burlington and Kitchener-Waterloo as part of Canada’s Innovation Corridor. It will connect to the Port of Hamilton and the Welland Canal, which provide multimodal transportation links to the St. Lawrence Seaway.

This project has been studied for more than two decades. It’s gone by other names too, such as the Niagara Frontier International Gateway and the Mid-Peninsula Transportation Corridor.

Of course, a new trade corridor won’t enhance Ontario’s competitiveness without game-changing investments at the border. The Peace Bridge is the primary Canada-U.S. trade gateway on the Niagara Peninsula. It is also a severe bottleneck. Built to accommodate 20-tonne trucks and 40-tonne trolleys, the Peace Bridge was processing over 7,400 vehicles daily before borders were closed in early 2020. The result has been long wait times, increasing the costs of doing business.

A strong case can be made for twinning the Peace Bridge given the location’s existing transportation, customs and security infrastructure. A second bridge would alleviate the border bottleneck for goods and people, as it can be anticipated that prior levels of congestion will have returned by the time this project is built. New border infrastructure will reduce trade barriers and facilitate the region’s important tourist clusters.

This project is at an early formative stage. Ontario should take on the mantle of advocate-in-chief, a bullhorn that focuses federal and U.S. attention on the economic potential of a second Peace Bridge.